Yulu Survey Results

Thank you!

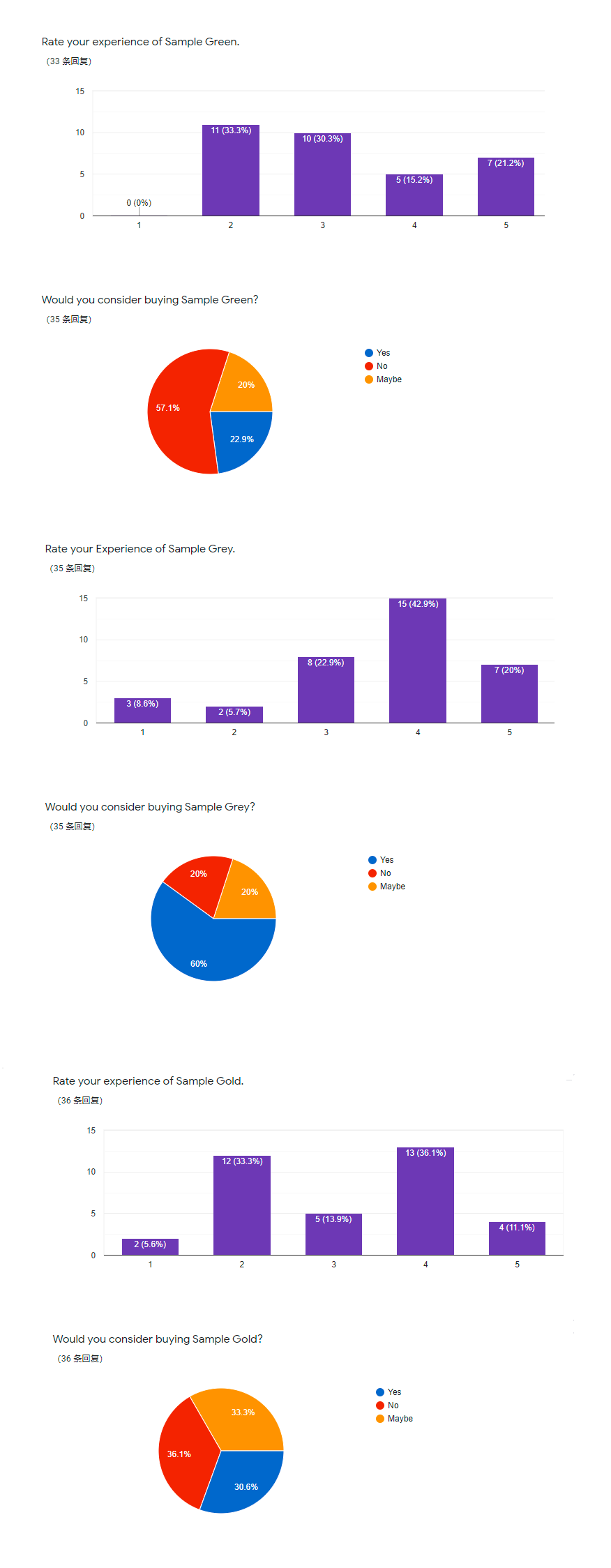

Between January 20th and May 31st, thirty six friends and customers answered our survey out of the 80 samples we initially sent. We deeply appreciate the support and attention we have gotten throughout this process and intend to follow up again next year. Click here for the full results. Bellow is our commentary.

The Teas

All of the Yulu teas in the survey were purchased in January 2021 from three different producers at the Selenium Tea Wholesale Market in Enshi, China. In order to be as objective as possible, we selected three producers we have had no prior or subsequent business with:

Baishaxi Cooperative - (Sample Gold) - Longjing #43 - Bajiao Township - 800 RMB/Jin.

Enlu Household Farm - (Sample Green) - Zhenong #117 - Tunbao Township - 380 RMB/ Jin.

Xinyuan Cooperative - (Sample Grey) - Longjing #43 - Xuanen County 850 RMB/ Jin.

Similarities

All of these picks came from one of the three principle sources of Enshi Yulu, however they are seperated by only dozens of kilometers. The climate and elevation are fundamentallly the same, however it is worth noting that Bajiao has a longer history of Yulu production and produces more Yulu by volume than any other township.

Ostensibly, all of these teas were also picked in the Mingqian tea season in late March of 2020 and were kept refrigerated. Additionally, they are all described by their producers as "Grade One," which means that their should be a relatively high degree of consistency in the thinness and legnth of the tea leaves, absolutely no twigs or other particles, and absolutely no harsh bitterness from improper steaming/drying. These three teas were all faithful to this grade.

Differences

The most glaring differences between these three teas is the varietal used. Neither Zhenong #117 and Longjing #43 are local to Enshi, but they have largely replaced the mixed heirloom varietals which are unsuited to unified mass production of Yulu. Zhenong #117 can deliver a greater yield to farmers, but the leaf shape, aroma, and color of Longjing #43 are generally higher rated in Yulu competitions.

Additionally there is also a difference in enterprise organization. Enlu is a small workshop ran by a single family that processes and sells tea from whichever neighbor carts it over. By not forming an official cooperative, the owner is potentially missing out on government funding assistance, but he does get to save on the management costs and profit sharing that cooperatives can entail. However, this also raises the odds that the tea leaves that go into the final product may come from plants that differ somethat in fertilizer support, overall health, age, and maybe even varietal.

Xinyuan's tea is the only one of the three to be fully organic and in line with the European Union's strict standads. Baishaxi is partially pulling from organic fields, and Enlu is drawing from Tunbao's certianly not organic "conventional" tea plots.

Finally, there is the question of official recognition. Baishaxi is an officially recognized Yulu producer. What that means is we can be absolutely sure that their tea production has been overseen by technicians that have trained in the traditional Yulu Style. The final product ought to be in compliance with the government-defined production standards.

Explanation of Taster Preferences

Our customers and friends showed a clear preference for Xinyuan's Enshi Yulu, ambivalence towards Baishaxi, and overall dislike for Enlu's. Baishaxi might be the one with the most guarantee of orthodox production, however Xinyuan also uses the same varietal and has a similiar scale of production. There is no reason it should necessarily be worse in quality.

The dislike for Enlu is easy to explain. It is price is a reflection of its divergence from the Chinese market preference for Longjing #43 and the relatively low cost of production. It is probably not a coincidence that the tasters in this survey agreed with Chinese preferences. Exactly half of respondents drink green tea every week, more than 55% of the respondents to this survey said they were very familiar (4 or 5 out of 5) with Chinese tea culture and 83% drank some tea daily. Maybe this suggests that these taster's preferences, knowingly or unknowingly, have been influenced by the standards set by the Chinese producers, technicians, and regulators. It could also be the case that the palate of boutique Western and Chinese tea drinkers are not as dissimiliar to begin with as some might assume.

Having not visited the Baishaxi and Xinyuan's cooperative's factories, we will not speculate on what might be behind the clear preference for Xinyuan over Baishaxi. Although it is a widespread marketing claim, we've seen no concrete evidence that organically grown Yulu is "sweeter" or "milkier."

What are we to make of those that most enjoyed Baishaxi's sample or gave a five star rating to Enlu's sample? It is possible that some folks may have been fast and loose with the temperature and proportions while brewing, but it is also true that there are individual outliers in experiencing taste and aroma. I recall once seeing a post by someone that really liked the taste of green tea that had been left unsealed for several years. That person's experience, while rare, should not be assumed as indicating poor taste or ignorance towards tea in general. It is also possible that tasters who cold-brewed these samples may have found the difference in aroma between Longjing #43 and Zhenong #117 negligable.